During their exploration of Northern California, millions annually come across a sign that reads “Russian River.” This prompts them, at some juncture during their travels in the heart of Sonoma’s wine county to ponder about the origins of the name of this splendid waterway.

Why is this major artery, flowing southwest for 110 miles from Mendocino County, near Willits, into the Pacific Ocean at Jenner, bearing the name of a country that is found thousands of miles away on a different continent? Perhaps old maps can tell us?

For thousands of years, this freshwater river has been called different names by the different people living along its picturesque shores. Pomo, Miwok and Wappo Native American tribes are just a few of the First Nations that lived on their ancestral lands along this beautiful stretch of California. The Pomo called the river ‘Ashokawna’, meaning east water place, or ‘Bidapte’, the big river. Other tribes called the river the ‘Shabakay’. The Spanish who settled Alta California in the 1770s referred to it as ‘Río Ruso’, ‘Río de San Ignacio’, and ‘Río de San Sebastián’. So why the “Russian River?”

During the “soft gold” rush era in the Pacific Northwest, the Russian American Company (RAC) began venturing into California on merchant vessels from New England trying to get their share of the lucrative sea otter fur trade which promised great profits on the Asian market. Eventually, the Russians began to scout the coast of California looking for a location to establish a commercial outpost to trade with the Spanish, engage in hunting, and secure agricultural and other provisions for the Company’s main operations in Alaska.

The task of finding an ideal settlement location, that was not physically controlled by the Spanish garrison out of the San Francisco Presidio, befell Ivan Kuskov, a Russian frontiersman with 20 years of experience in Alaska. Kuskov led a number of expeditions (1808-1812) from Alaska to California searching for a place with decent anchorage, an abundance of forest, and freshwater. The first makeshift camp, built by the Russian American Company’s settlers in Bodega Bay in 1809, was soon renamed Port Rumyantsev, in honor of the Chancellor of the Russian Empire. It is from Port Rumyantsev that Kuskov ventured inland again in 1812 until he came across the valley of the river that he named ‘Slavyanka’. ‘Slavyanka’ literally translates as ‘female Slav’. (See ‘A Historical Note about the Russian Settlement on the Coast of New Albion’, Document 291, published in Russian California, 1806-1860: A History in Documents, Hakluyt Society, by James R. Gibson, Alexei A. Istomin.)

Kuskov achieved his task and soon founded Settlement Ross on the ancient Kashia Pomo lands. Kuskov “undertook a survey of sites for a settlement. The prikazchik Slobodchikov and the apprentice navigator Kondakov with ten Alaska Natives were sent on foot from Bodega to the Slavyanka River, and Kuskov himself kayaked up the river. A suitable site for a settlement was not found anywhere, and for that reason, Kuskov decided to establish the colony fifteen verstas north of the mouth of the Slavyanka River on a small cove’ in 38°33´N latitude and 123°15´W longitude, where all of the men were moved with the ship.” (‘A Historical Note about the Russian Settlement on the Coast of New Albion’, Document 291, published in Russian California, 1806-1860: A History in Documents, Hakluyt Society, by James R. Gibson, Alexei A. Istomin.)

The new settlement called Ross, in honor of Russia, became the main center of the Russian American Company’s operations out of California with Rumyantsev Bay serving as the main port. In the Company’s papers Fort Ross, also known as Settlement Ross, was sometimes referred to as “Slavyansk” in reference to the Slavic culture, predominantly East Slavs, chiefly Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians.

Slavyanka River valley played an important role in the Russian exploration of the interior and a vital role in a relationship with the First Nations. The natives who maintained regular contact with Settlement Ross belonged to three ethnic groups and all of them had ties to the river which was now navigated by the Russians and Alaska Natives. Close neighbors at Fort Ross were the Kashia Pomo, who for thousands of years have inhabited the coast approximately between the Slavyanka and Gualala Rivers. To the southeast of Fort Ross in the Slavyanka River Valley lived the Southern Pomo and to the south around Bodega Bay the Coast Miwoks.

By the 1830s, Fort Ross settlers expanded their agricultural production southeast and moved in to established farms (ranchos) around the Slavyanka River. The 100 acres of Kostromitinov Rancho, founded in 1833, was based at Willow Creek just above its junction with Slavyanka River. Khlebnikov Rancho also opened in 1833 in the upper valley of Salmon Creek some five miles east of Port Rumyantsev, and New Rancho was established in 1838 some ten miles east of Port Rumyantsev.

During the Russian tenure in California, the river was always referred to as Slavyanka by the Russians and even by some European cartographers. The reference to Slavyanka River was still being used in some European maps long after the Russians abandoned California in 1841. Even the Russians themselves referred to their former Californian claims by their Russian names as late as 1845.

While conducting research for this publication, I had the great pleasure of studying old maps of Alta California. And here is some of the information I managed to discover while delving into the subject.

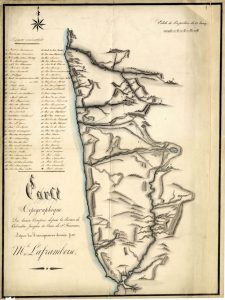

In the 1830s, French Canadian fur trader, Michel Laframboise, one of the founders of Fort Astoria, the primary fur trading post of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company (PFC) at the entrance of the Columbia River, ventured into the Oregon Country and Alta California where he compiled a map, which included a number of Russian named places, which have long been lost to history, among them the Slavyanka River.

On Laframboise’s map, the ‘Slawjanka’ River flows from ‘Lac Russe’ [Clear Lake] westwards to the ocean. He also notes that Gualala River used to be called the ‘Costromitinoff’ River during his sojourn in California.

The Mexican authorities, who never recognized Captain John Sutter’s claims to the land after his purchase of all immovable Russian property from Fort Ross, divided the formerly administered Russian American Company’s land into separate land grants. Rancho German and Muniz Rancho were allocated to the North of the Slavyanka River, while Russian farmlands around the main harbor (now called Bodega Bay) became Estero Americano and Rancho Bodega. Jean Jacques Vioget, a Swiss-born cartographer who also happened to witness the transfer of Russian property to his fellow countryman Captain John Sutter, drew the boundary of the Muniz land grant, calling the Slavyanka River – Río de San Ignacio.

Other maps, from the time of 1830s – 1850s, simply showed a lack of understanding of the Californian coast. This is true for the United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842) map, and ‘Map Of Oregon And Upper California From the Surveys of John Charles Fremont’ of 1848. Even the 1849 “Life, Adventures, and Travels in California” map developed for the gold seekers did not include any references to one of the first major rivers north of San Francisco Bay.

Confusion over the name of the river as well as the boundary of former Russian claims persisted well over a decade after Fort Ross was abandoned by the Russians, and even after the conclusion of Mexican–American War (1846-1848) which ceded Alta California to the United States. The huge influx of migrants flocking to San Francisco from Europe on board ships at the height of the Gold Rush still had maps at their disposal with different names for the same geolocations.

For instance, an Italian map from 1851, still showed Russian possessions in California, including ‘Altravoltre colonia’ of the Russians and ‘Kostromitinoff’ farm on the river, which the map refers to by one of its Spanish names – San Sebastián. Two separate German maps published by two different publishing houses in 1855, referred to the same body of water both by its Spanish name and the recently adopted American term – “Russian River”.

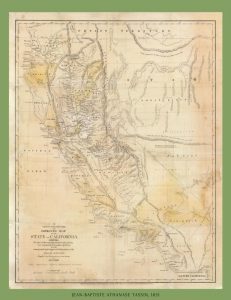

The term “Russian River” was arguably enshrined in cartography by Jean-Baptiste Athanase Tassin (1800-1868), a renowned French lithographer, and US government geographer, who arrived at San Francisco just after California joined the Union to become the 31th state. His 1851 map, published in San Francisco by Cooke and LeCount, for the first time, referred to the waterway formerly controlled by the Russian American Company as the “Russian River”.

Newspapers in San Francisco started using the term “Russian River” immediately after the United States secured victory over Mexico. It appears that Tassin simply adopted the most commonly used name for this river at the time when he was conducting his surveys for the US government. Newspaper references suggest that Captain Stephen Smith (1782-1855), from Massachusetts, who settled in Bodega Bay after the Russians left port Bodega (Rumyantsev), could allegedly be the culprit responsible for propelling the term “Russian River” in local publications.

It is safe to assume that the Russian River was named in honor of the Russian American Company explorers who first charted the area. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Russian River became a popular destination for tourists, who were drawn to its natural beauty and the mild climate of the region. Many visitors, including members of the Russian-American community, built summer homes along the river, and the area became known as a resort getaway.

Today, the Russian River remains a popular destination for visitors to Northern California. The region is home to a variety of outdoor recreation opportunities, including hiking, kayaking, fishing, and camping. The towns along the river offer a variety of dining, shopping, and cultural experiences, and the region is known for its wineries and craft breweries.

From its indigenous roots to the Russian fur traders and the development of a resort community, the river has been shaped by many different influences over the years. Today, visitors can enjoy the natural beauty and cultural richness of the region, while also appreciating the history and legacy of the Russian River. The legacy of the Russian presence can also be seen in the architecture of Fort Ross, which is now a State Historic Park.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.